Theodore Fleet

THEODORE B. “THEDY” FLEET

1866-1946

POTTER

CHUCKY VALLEY, TENNESSEE STRASBURG, VIRGINIA

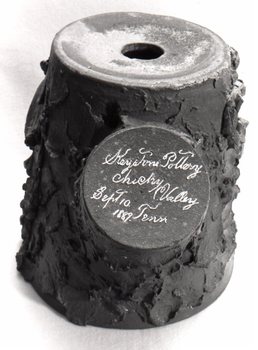

An early puzzle encountered in the study of the Decker pottery was a very curious and quite different piece bearing the signature of “T.B. Fleet”. See illustration 29. None of the present generation of the Decker family recognized the name and they had no information as to what connection he might have had with Decker’s pottery operation. Since the vessel also bore the inscription “Keystone Pottery Chucky Valley Tenn Sept 10. 1889” (illustration 30) and the name “C.F. Decker” in applied clay letters around the body, it was apparent that Fleet was the maker and that it had been made as a presentation piece for Charles F. Decker, Sr. When found in the back yard of Bella Decker Phipps, a granddaughter of Charles Decker, it was being used as a flower pot as shown in illustration 31na. This could hardly have been the intention of the potter since Decker’s name and both inscriptions were upside down. When reversed as in illustrations 29 and 30 the lettering became legible but it could no longer be used as a flower pot. The theory that it must have served as a base or stand for another piece was reinforced by a rather well defined wear ring on the top. When questioned Mrs. Phipps recalled another similar but larger piece which had gotten into the hands of a Jonesborough woman a number of years earlier. Mrs. Phipps could not remember her name but recalled that she had worked in a bank. Upon inquiry it was learned that the woman had retired and gone to Washington, D.C. to live with a daughter whose name the banker could not remember. No further trace of her — or the flowerpot — could be found. Mrs. Phipps remembered it as having been made to simulate a section of a tree with applied “bark” similar to that on the stand. It had other decoration as well but Mrs. Phipps could not recall its nature other than that it too had Decker’s name in applied letters. It seems certain that it was a companion piece made by Fleet to go with the stand.

Flowerpot base formed to resemble a tree stump. C. F. Decker is applied in letters made to look like bark covered limbs. T. B. Fleet is incised in script on a flat area which simulates a limb having been cut away. illus29.

Another view of the flowerpot base which resembles a tree stump. Keystone Pottery Chucky Valley Tenn Sept 10. 1889 is incised on a flat area which simulates a large limb having been cut away. illus30.

A possible clue to Fleet’s identity was found in Rice’s book “The Shenandoah Pottery,” published in 1929. In a chapter on the Eberly Pottery of Strasburg, Virginia, it is stated that “Theodore Fleet returned to Strasburg and entered into their employ.” No date is given nor is there a clue as to the place from which he returned. Since no middle name or initial was stated, could it be safely assumed that “Theodore Fleet” of Strasburg was “T.B. Fleet” of Chucky Valley? A check of cemeteries in Strasburg located a stone reading “Theodore B. Fleet 1866-1946 At Rest.” See illustration 32na. This indicates that Fleet would have been twenty-three years of age when he made the flowerpot stand found at Mrs. Phipps’ home. Was he too young to be working so far from home? We must remember that in those times Fleet had probably started work in one of the Strasburg pottery shops in his early teens if not even earlier. We also know that it was not uncommon for a journeyman potter to seek work in potteries in other areas. Certainly word of a pottery as large and as successful as Decker’s would have reached Strasburg, the pottery center of the upper Shenandoah Valley. Fleet’s decision to come south to Tennessee to seek employment may also have been influenced by the difficulty of finding work at home.

Other questions remained, namely, when did he begin work for Decker and how long did he continue to turn ware for him? A few weeks after finding the stand a search of a storeroom in the Decker homeplace turned up several account books, ledgers and financial records from the pottery operation. Although fragmentary and lacking in early records from the 1870s and late records from the early 1900s, several ledgers and records from the 1880s and 90s furnished invaluable information on the types and amounts of ware made and sold; names of potters employed and the sums paid them on a “piecework” basis; names and locations of customers; board charges to potters; amounts charged for medical and veterinary services; variety and prices of goods sold in the store, etc.

Large low flowerpot with four applied rings around the sides after restoration by Andrew Hurst. illus33.

The ledger for 1889 and 1890, page 27 shows that T.B. Fleet “commince” work on August 9, 1889. By August 12 he had turned 200 one gallon jars for which he was paid 2 cents each. By August 14 he had produced 100 jars, 1/2 gallon in size for which his account was credited with $1 or 1 cent apiece. On the 15th $2 was credited for 100 one-gallon jugs and so it went until October 25 when he paid his board bill at the Decker home of $2 per week, his account at the nearby Decker store for $28.40, and left with a check for $22.93, his profit for 10 weeks of hard work. “Sweatshop wages, not enough!” you may say. Remember, he paid board of only $2 per week for three meals per day — about 9 cents per meal. Of his account at the general store of $28.40, a total of $21.25 was for cash advances on such occasions as a “picnic at Embreeville.” Store purchases were for such things as a box of cartridges for 40 cents and a box of cigars for $1.25.

There is no record of why he left or where he went but the ledger notes that Fleet “came back on Nov. 7/89.” The record of his production continues until October 1, 1890 at which time his employment by Decker appears to have ended. The time he worked for Decker is of less importance than the number and types of ware which he produced. The number of pieces turned gives us an idea of his skill and speed while the types of vessels made gives us good evidence of the demand for various shapes and sizes of pottery.

BY THEODORE B. FLEET FOR DECKER

| JARS | JUGS | CROCKS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | Number | Size | Number | Size | Number |

| 3 gal. | 17 | 2 gal. | 310 | 2 gal. | 200 |

| 2 gal. | 235 | 1 gal. | 3,565 | 1 1/2 gal. | 360 |

| 1 gal. | 1,235 | 1/2 gal. | 849 | 1 gal. | 4,386 |

| 1/2 gal. | 1,371 | 1/2 gal. | 3,557 | ||

| Totals | 2,858 | 4,724 | 8,503 | ||

| PANS | PITCHERS | JELLY MUGS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | Number | Size | Number | Number |

| 2 gal. | 25 | 1 gal. | 60 | 100 |

| 1 gal. | 50 | 1/2 gal. | 80 | |

| Totals | 75 | 140 | 100 | |

TOTAL OF ALL TYPES: 16,400

Plus 1 day making tile

1 day making pipes

To determine his approximate daily output the period in late October and early November 1889 during which he was away from the pottery must be deducted. So, too, must 52 Sundays plus an unknown number of other days when the pottery did not operate for various reasons. The number of pieces turned is also lacking his output as recorded on a page in the ledger which was assigned to him but which was missing. It is certain from the above figures, however, that he worked hard and fast for long hours. When one man in one year turned over 16,000 pieces how could it possibly be so difficult to find items from the Keystone Pottery today? When we consider that the pottery operated over thirty years, at times with three or more people turning ware at once, it seems absolutely incredible that so much could have become so scarce —even in the almost one hundred years since the pottery closed. On the other hand we must remember that 99% of the output was utilitarian, cheap and breakable. Light and easily cleaned glass canning jars replaced the heavy and rough-surfaced stoneware jars which had been a staple production item. Heavy and clumsy stoneware crocks and jars gave way to glass and tin. Flowerpots froze and cracked with newer materials and styles available as replacements. The liquor distillers gradually shifted from stoneware jugs to glass jugs, fruit jars and bottles. There were no compelling reasons to save the stoneware jugs, jars, crocks, etc. The exceptions were the special pieces which were decorated and signed by their makers. The base for a flower pot which is shown in illustrations 29 and 30 is certainly such a piece. With the name of the maker, the place and date made, and the name of the person for whom it was made, it ranks as one of the most completely documented pieces of American pottery which is known.

Another distinctive piece now attributed to Fleet was not recognized as such for several years after the study of the Decker pottery was begun. In the beginning the present generation of Deckers who still lived in the area were interviewed.

Lutora Decker Barnes, one of Dick Decker’s daughters, lives across the highway from the present Decker store, the pottery site, and the original Decker home. In her side yard major pieces of a very odd flowerpot were found scattered over an area about twenty feet square. The pot was wholly unlike any of those produced at the pottery for sale to the public, being wide, shallow, striped to simulate tree bark, and decorated with four large applied rings around the sides. It was photographed after restoration by Andrew Hurst, preservationist at the McClung Museum, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville. See illustration 33. Unfortunately it bore no signature. It was assumed that it was either a “special order” piece or that one of the Deckers made it for family use.

When Fleet returned to Strasburg and began work for the Star Pottery owned by Jacob Jeremiah Eberly he met a potter who was to teach him a new skill and change completely the type of ware he had turned for Decker. An English journeyman potter named Levi Begerly had somehow found his way south and had joined the turners working for Eberly. He brought with him the knowledge of mold making which he taught to Fleet. Thereafter Rice reports that the manufacture of stoneware was discontinued and only “fancy ware” was produced in which molds were employed to decorate the pieces with flowers, birds, sunfish, lizards, foliage, etc. This new dimension of decorating pottery at will must have been a pleasure for Fleet after years of making purely utilitarian pieces with the one being turned simply a duplicate of the one just finished and a model for the one to follow. Begerly returned to England after a few years and Fleet demonstrated ingenuity in using things about him to create his own molds for decoration.

Rice reports that on one occasion Fleet killed a large black snake and after placing it in a coiled position, he made a plaster of Paris mold in which he made rather realistic pottery door stops. Perhaps they were too realistic for few were made. Someone caught a nice sunfish in a nearby stream and Fleet’s mold of it appears on the side of flowerpots and other vessels. Even a lizard which foolishly crawled into range of a mud ball thrown by Fleet is immortalized in clay on the sides of flower vases. In addition to molded decoration much of the ware was in a variety of colored glazes made from formulas obtained from Fleet’s father, a skilled potter named Lorenzo, who had worked for members of the Bell family of potters.

The Eberly pottery closed after the suicide of Jacob Jeremiah Eberly in 1906. His second wife, who was a great deal younger than her husband, apparently had the contents of the pottery moved to her home on the corner of Capon and W. Washington Streets in Strasburg. A great many molds, including many undoubtedly made by Fleet, were stored in the basement along with a large variety of pottery. Other pieces of pottery were scattered throughout the- house — everything from bean pots to umbrella stands. Mrs. Eberly, the house, the pottery and the molds “stayed put” for the next seventy years. Following Mrs. Eberly’s death in 1976 at the age of 108 the house and contents were sold at auction on June 19. The sale was held by two local auctioneers, one of whom had a severe speech impediment which made him even more difficult to understand than the usual jargon employed by country auctioneers in the hope of exciting the crowd. Neither man knew anything about the pottery and molds which they had been commissioned to sell. The fact that both auctioneers were selling simultaneously at different points in the back yard added greatly to the confusion. A blazing summer sun, no shade, no seats and no rest rooms added physical discomfort to the occasion. The spectacle of seeing over 100 pieces of pottery produced by a leading Strasburg pottery almost three-quarters of a century earlier being sold under such conditions is one not likely to be forgotten. Illustration 34na shows one of the auctioneers selling from the back porch of the Eberly house. It fails to convey the noise, confusion and heat. Some of the great molded pottery which went “under the hammer” is illustrated in illustration 35na. Note the castles and church which decorate the four-paneled base of the large three-part flowerpot or vase. The center section is a molded tree and trunk and the bowl at the top is in the form of a large seashell. Illustration 36na shows four of the molds made by Begerly and Fleet in which “fancy ware” was made. Those shown, like many of the molds stored in the dirt-floored basement, had been damaged by water which apparently stood in pools the year round.

The rather long drive from the author’s home in Knoxville to the sale in Strasburg was made in the hope that additional evidence connecting Fleet’s work for Decker with that done later for Eberly would turn up in the Eberly sale. One of the first objects seen in the basement of the Eberly home was a very odd flower pot which was wide, shallow, striped to simulate tree bark, and decorated with four large applied rings around the sides. (See illustration 37na.) Bingo! A mental image of the flower pot found years earlier in Lutora Barnes’ side yard flashed on my memory screen and the flowerpot from the Eberly basement came to Tennessee for cleaning and restoration. The two are pictured side by side in illustration 38na. The one made for Mrs. Decker is on the left and it is slightly smaller than the one made later for Mrs. Eberly — no doubt the first Mrs. Eberly. The one given to Mrs. Decker has an added ring of decoration near the base but otherwise the two are identical in form and decoration. Each has four of the applied rings around the sides. No other similar ones have been seen which could have come from either the Decker or the Eberly potteries. No similar ones have been seen which were produced at any other pottery. It is safe to conclude that Fleet made similar presents for his employers’ wives in East Tennessee and Virginia.

It is fortunate that Fleet found time and energy to produce at least three distinctive pieces of pottery while working in Decker’s Keystone Pottery. However, they do not afford a really true basis for measuring his creative talent. The 3-part, 40-inch flower vase or pot shown in the center of illustration 39na is considered to be one of the most beautiful and dramatic pieces of molded pottery produced in America. Fortunately it went to the Strasburg Museum where it may be seen along with the molds in which it was cast. Fleet and Begerly also collaborated on what Rice called “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” He described it as a “masterpiece.” Dr. H.E. Comstock, preeminent authority on Shenandoah Valley pottery, of Winchester, considers it to be “no doubt one of the most imaginative pieces of American folk pottery sculpture.” A man, woman and child are seated in front of a one-room log cabin. A dog stands beside the child and there is a windlass for drawing water from a well. Made in 1894 to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the nearby Civil War Battle of Fisher’s Hill, this great little piece is stamped “J. Eberly & Co., Strasburg, Va.” It is unfortunate -although understandable - that the pieces made by Begerly, Fleet and possibly other employees of the Eberly shop were almost never signed with their name. As the owner of the business Eberly had a right to insist that the company name be stamped on pieces to be marked. However, Eberly was not a potter. Fine and creative pieces went out with his name but were never touched by his hand.

Some indication of Fleet’s significance in the story of Strasburg pottery may be gathered from the fact that there are eleven references to him in Rice’s book. The forthcoming book on Shenandoah pottery by Dr. Comstock will undoubtedly bring to light additional interesting facts on the work of “Thedy” Fleet.

Editor’s note: only a small number of photographs accompanied the essays. An effort will be made to obtain the missing images for this site. For the present, poor quality images were deemed better than no images. An na indicates that no image was available. An si indicates that it is a substituted image. If the source of the substituted image was Beverly Burbage a BB will be affixed. An ai indicates that it is an added image. If the original source of an added image was Beverly Burbage then Burbage will be added to the image caption.

Copyright 2009-2022, Carole Wahler

Site by GearheadForHire, LLC | v1.0.2